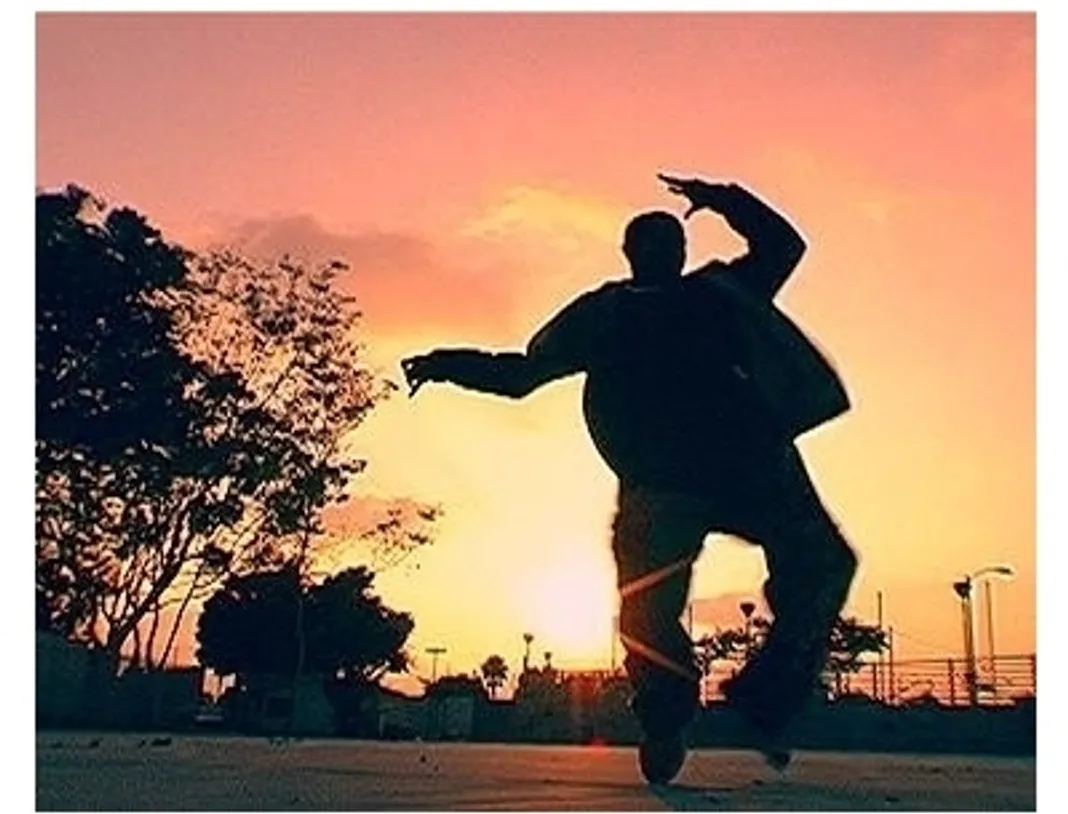

Beginning in 1992 after L.A.’s Rodney King riots a reformed ex-convict named Tommy Johnson needing a job grabbed a boom box some face paint and a clown suit. Bizarre yes. But he started a successful kids’ party business dancing in the riot-ravaged areas. Before he knew it Johnson–who named himself Tommy the Clown–started a ghetto-wide trend of “clowning ” and later “krumping ” both characterized by quick sudden dance moves. Rize is about more than just Tommy the Clown of course. It’s about race and oppression in America and the therapeutic effect of dance throughout the centuries. The film attempts to channel the human spirit through physical expression as the real-life faces give Rize extra needed impact to the oppressive story–one unfortunately that is all too familiar.

The real-life street dancers infuse the documentary. They are essentially characters with alter-ego names like Dragon Miss Prissy and El Nino. Decorated in face paint they are average real South L.A. “hood” residents with average jobs. Larry for example still works at Abercrombie & Fitch. But boy they can dance. LaChapelle‘s visual storytelling elevates them to iconic actor-like character status. More gravely however the dancers’ belonging to clown or krump crews often substitute gang affiliation in the bombed-out neighborhoods. Rize works because of its “acting ” the vibrancy and timelessness of its characters’ spirits.

Paris Hilton and Pamela Anderson‘s good friend David LaChapelle directs his first feature after he released a similar short film Krumped last year. His celebrity portraits have graced Vanity Fair and Interview magazines since the ’80s. We last saw LaChapelle on the police blotter in January getting arrested for disorderly conduct. Utah police allege LaChapelle who was partying with Hilton and Anderson at Sundance where Rize premiered became physically and verbally abusive when separated from the starlets. The case isn’t settled yet. But in light of these charges it could be LaChapelle‘s ability to bull his way through filming glossing over themes quickly that gives Rize its broad-brush impact. LaChapelle offers a different documentary in the post-Michael Moore era–one without a political point of view or wry scrutiny of shady characters. Instead LaChapelle (who apprenticed under Andy Warhol) sees himself more as an artist. With Rize he’s molded an artistic topical statement a timely bull’s eye of hip-hop and Blue State progressivism. The filmmaker trains the audience’s eye quickly to become hypnotized in the dancers’ bodies and to seek higher meaning.