Few directors have eclectic enough resumes to be deemed truly unclassifiable, but that’s John Landis. In his 30+ year career, he’s directed some of the scariest horror movies (American Werewolf in London) and funniest comedies (The Blues Brothers, Animal House) of all time. Landis has a passion for filmmaking and movie-watching—and he hasn’t been shy in playing with some of his favorite genres during his lengthy career.

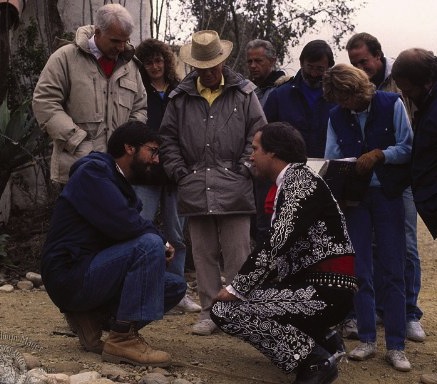

Coinciding with the Blu-ray release of his 1986 Western comedy ¡Three Amigos!, I had a chance to sit down with the director and discuss the movie, the zounds of extras featured on the new disc and explore the bumpy road Landis has faced working in the Hollywood scene:

I got to check out the ¡Three Amigos! Blu-ray last night. It’s a phenomenal disc. There’s so much stuff on it that I didn’t realize was missing from the original movie.

I got to check out the ¡Three Amigos! Blu-ray last night. It’s a phenomenal disc. There’s so much stuff on it that I didn’t realize was missing from the original movie.

John Landis: Well, it’s not really missing. When you make a movie, you always—I can’t think of any movie but [Hitchcock’s single-take film] Rope where they didn’t cut stuff out of it.

But it sounded like some of the footage actually ended up disappearing. Some of the stuff that you cut.

JL: Well, what happened is, that was made for a company called Orion, and Orion went out of business. So, unfortunately, when film companies go out of business, the negatives get shuffled around from lab to lab. And now the picture is owned by Warner Bros. And they had the negatives. And I had the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences store all my prints. And I had a print of the second preview. So that had a lot of stuff that was cut out. Unfortunately, we just couldn’t find the outs and trims of the Sam Kinison stuff and the Fran Drescher stuff, which I was sorry about.

Yeah. Can you talk about why that didn’t make it into the original film in the first place?

JL: Mainly for time. The movie was too long. And Sam and Fran, they were sequences that you could lift out of the movie and not impact the plot.

Sure. Were they irked? Were they like, ‘Where are we!?’

JL: They were disappointed, I think. Sam I had a good relationship with, and he completely understood.

How did you come into this project? I know that Steve [Martin] wrote the movie—

JL: With Lorne Michaels and Randy Newman.

Right. And how did you get involved, and what was the hook that was really drawing you into doing ¡Three Amigos!?

JL: Steve called me and said, ‘I have a project. Would you be interested?’ And I said, ‘Send me the script.’ And when I saw it was a Western, I immediately went, ‘Yes, please!’ I mean, I love Westerns. And it’s the only Western I’ve directed. But I’ve worked on a lot of Westerns, in Spain, and Durango. And I love the genre. So, even though, it’s a comedy, it was a Western. And you get to ride around on horses. It was fun.

Did you get to ride around on horses?

JL: Sure! I used to fall off horses for a living!

At what point in your career were you falling off horses for a living?

JL: I was a stunt person for years! After Kelly’s Heroes, where I was a gofer, I went with a guy named Jim O’Rourke. We went to Spain—that’s 1969—which was right in the middle of the Spaghetti boom. And they were making—gosh, I lived in a town called Almeria, and sometimes Madrid. In Almeria, there were always at least four and sometimes as many as ten productions going. It’s a desert town, near the ocean…I worked on Once Upon a Time in the West, and A Town Called Bastard. And just a lot of Westerns!

They needed a guy to fall off horses, and you were the guy.

JL: They needed a lot of guys to fall off horses. But I got very good at it, actually.

Is that how you kind of transitioned into directing? Through stunts?

JL: No!

I imagine something like, ‘Hey, I’m really good at falling off horses! Let me direct a movie!’

JL: [Laughs] Yeah. That’s funny. People sometimes write that: ‘I started in the mailroom, and worked my way up.’ Which makes no sense! It’s not the military! That’s not how it works! [Laughs]

Working on this movie with these three big, strong personalities, comedic forces…what was it like?

Working on this movie with these three big, strong personalities, comedic forces…what was it like?

JL: Actually, this movie was a pleasure from start to finish. Because it was a funny script, and Steve and Marty [Short] and…well, Steve and Marty met on the movie, and they’re still best friends. But Steve and Marty and Chevy [Chase], they take care of one another. They’re busy topping one another all the time. [Laughs] And it was a pleasure! There were no problems on this picture. And I really wanted it to look a certain way. I wanted it to look like a big Technicolor Hollywood Western of the ‘50s. So, the production designer, Dick Sawyer, and my wife, Deborah Nadoolman, the costume designer, went to a lot of trouble to make it right. And so, that’s why I was so happy with the opportunity to restore it to the way it’s supposed to look.

What was that process?

JL: What they do when you make a Blu-ray, they scan the negative. They learned this when they started to do high-def…but I’m not going to explain this in the correct terminology. These are not the right words.

No one will scrutinize you, trust me.

JL: Basically, you know what bits of information are? Like, a gigabyte?

Yeah! Absolutely!

JL: Okay…because I don’t. When you have a film negative, you have a 35mm negative that was shot on film and developed chemically, it turns out that by chemical processing, you only got about fifty-five to sixty percent of the information that’s on the negative. So when you scan it digitally…it’s very similar to what happened when they took the old mag stripes, and then digitized them, and redid the old Beatles tunes. They discovered that you could hear conversations in the hallway of the recording studio. There was so much more information on the stripe than they knew. And in ¡Three Amigos!, it looked gorgeous if you saw it in the first run. But after a while, prints get ragged. And home video, they just took off some release print that had seen a lot of work and had scratches in it, and was faded. So, I was very happy to be given the opportunity to restore it. Make it look the way it is supposed to look. Because we were trying to make it look like old pre-strip Technicolor.

Well, it definitely pops on the Blu-ray. I’ll say that. Was it just a straight-up retransfer?

JL: No, no, no! It’s a long process! You sit with the technicians and you go through every frame.

Oh, so this was a hands-on process for you.

JL: I didn’t do the…there’s, like, three weeks work before I get there where they remove all the scratches and blemishes. They just remove all that. Make it nice. And then—sometimes too nice! Sometimes I make them put stuff back. But then I come in and supervise the color timing, and the tonalities and stuff. And that took about two weeks.

It’s interesting to go through that process with a comedy. I think there’s a mentality that comedies don’t need to look sharp because they’re all joke, joke, joke. But it’s a film, and it should look good. And obviously, the design of the film to echo those older films was important to you.

JL: I always feel that that stuff is important. I don’t know if you notice, but a movie like Animal House—everybody thinks it was a raucous comedy, but it also happened to be a period picture.

Sure.

JL: It was [set in] 1962, and we went to a lot of trouble to make it right. And Trading Places, or Spies Like Us, all those moves. I go to a lot of trouble to make them look good. In fact, sometimes I get—I remember with Spies Like Us, which I wish they would do a Blu-ray of, but I doubt they will—but on Spies Like Us, when the picture came out, I remember so well being punished because it looked too good. Charles Champlin, he was an LA Times critic, he wrote a piece talking about profiting in Hollywood. And he used the example of the way to make a movie: Back to the Future, which was shot entirely on the lot of Universal. And that is a wonderful movie. But his point was, ‘Then there’s Spies Like Us: this stupid comedy, where they were in four countries, went all over the world…’ And, you know, what Champlin didn’t understand was, we were in four countries because it was cheaper! In fact, Spies Like Us cost, like, one fifth of what Back to the Future cost.

That’s not even a criticism!

JL: Most critics don’t…

Don’t I know it. Thinking about finding the right balance of comedy—how do you know what’s funny? Is it all instinct?

JL: That’s just, ‘Is it funny to me?’ That’s all. And the thing with the three guys, they’re playing these characters…and what I liked in the script, and what I hope I captured in the movie, is that it’s a very different type of comedy than contemporary comedy. It’s much more like Laurel and Hardy. Because they’re sweet! They’re childish! They’re not mean! There’s no meanness in it.

Do you think today’s comedies are meaner? Different than what you were producing a few decades ago?

Do you think today’s comedies are meaner? Different than what you were producing a few decades ago?

JL: No, I mean, I enjoy Bridesmaids. I thought that was funny. There are comedies made that I think are funny.

That’s a relief. But do you feel like the landscape has changed for comedy?

JL: Well, the whole business has changed! It’s a very different time. The people, the studios. One: filmmakers aren’t given the freedoms we were. And two: everything’s committee now. It’s all corporate. And it’s about marketing and merchandise. It’s really about trying to control the filmmaker. It’s a different time. It’s just a different time in the business. I mean, good movies will continue to be made. But fewer and farther between.

Sure. Switching gears—I was watching an interview on the new disc, a conversation between the three guys and some studio person doing EPK footage.

JL: I don’t know what the hell that is.

Yeah. It’s a bizarre little interview.

JL: It’s bizarre because it’s clear they don’t want to be there.

[Laughs] No one’s prepared, including the interviewer, which was pretty amazing. But it’s candid. It’s interesting. Steve mentions in the interview that a sequel seemed like an inevitable thing to him. Or that one was always planned. This was a franchise to him.

JL: I don’t know. It is true that we all had a wonderful time making the movie. It was really fun. And it was pain-free, and it was a pleasure. You know, Walter Hill once said, ‘If they knew how much fun it was to make a Western, they wouldn’t let us.’ And I had such a good cast: Alfonso Arau and Tony Plana. Jorge Cervera. Joe Mantegna. I think it’s his first movie, Joe Mantegna. And it was just so much fun. And I know that Steve and Marty and Chevy just had the time of their lives, and I think they just wanted it to keep going. [Laughs]

Would you return to directing a straight-up comedy?

JL: Oh, of course!

Is that something that you have in the works?

JL: Well, you know, I tend to like wacky stuff, and the studios tend to be pretty formulaic now.

Would you ever go indie routes outside the studio?

JL: Oh, I have!

JL: Well, American Werewolf in London was independent. Kentucky Fried Movie was independent. And my last, Mr. Warmth, I made with my own money. You know, because no one would give me the money. So…I’ve been independent for so long!

Thankfully. Is working independently helping you bring your current projects to life? Do you have anything in the works?

JL: Oh, sure. I’m always trying to…right now I’ve got a comedy I’d like to make. But you know what happens when you’re successful, when something is successful? It’s instantly mainstream. No matter how radical it is. Like, rock and roll was the ‘devil’s music’ and race music, until they saw, ‘Wait a minute, look at the money this is making.’ And then it became big business. It’s very similar—I’ve been very lucky, because a lot of movie’s I’ve made, which were extremely radical at the time, were successful. I mean, they were shit on by the critics, but they were very successful. And when you become successful…people don’t look back at Animal House, or The Blues Brothers, or those pictures as out there as they were. [Laugh]

I don’t think anyone could see something like Blues Brothers being made today. Then again, you made a sequel to that movie.

I don’t think anyone could see something like Blues Brothers being made today. Then again, you made a sequel to that movie.

JL: That was my last studio picture, because I had never experienced the new studios, where they fuck with you. And they cut your movie and basically fuck it up. That was very shocking.

Was Blues Brothers 2000 not a good experience for you?

JL: Well, shooting it was fun. The problem with Blues Brothers 2000 was, I don’t think the studio…Danny [Aykroyd] and I wrote a wonderful script. And for Danny, it was all about the music. ‘We must get these people on film.’ Ironically, he’s not wrong. I look at the movie now, and so many of those guys have passed away. So, we did put them on film.

Immortalize them, yeah.

JL: And the music is awesome, and most of it is recorded live.

Really?

JL: Yeah, because we could do that with the new technologies. Ninety percent of Blues Brothers 2000 is live. What happened to us was, the management that hired us to make the movie then was ousted, so we had new people come in. And they did not want to make the movie. And they kept giving us notes. By the time they were finished with the script, John Goodman had no character. And they insisted on a boy, and then insisted on a black Blues Brother…and it got to the point where I said, ‘Danny, they just castrated this movie!’ And Danny was, ‘It’s about the music with this.’ And our producer, Leslie Belzberg said something that was true. She said, ‘If you don’t cooperate, if you don’t say ‘yes’ to every note, then they won’t make the movie.’ Which was fine with me, but Danny was like, ‘We must [make the movie].’ And I love Dan Aykroyd. He’s a great person. So, we made the movie, and then they fucked with it! They even retimed it! I mean, that movie didn’t look like that!

It doesn’t even look the way you wanted!

JL: No! Look at The Blues Brothers, look at that! One is all like a Doris Day picture, and the other is dark and gritty. But The Blues Brothers 2000 has spectacular music in it, so I’m very happy.

You mentioned that you have a comedy that you’re looking to direct. Is there anything else that you have in the works?

JL: I think that I’m going to be making this very strange little monster movie in Paris next year.

A monster movie?

JL: Yeah. In French and in English.

Ooh!

JL: Two versions of it.

Can you tease at all?

JL: Well, it’s not like other monster movies. It’s a monster. It’s a real monster, and it takes place in Paris…which allows me to tell you, please mention my book that I just did!

=”font-style:>