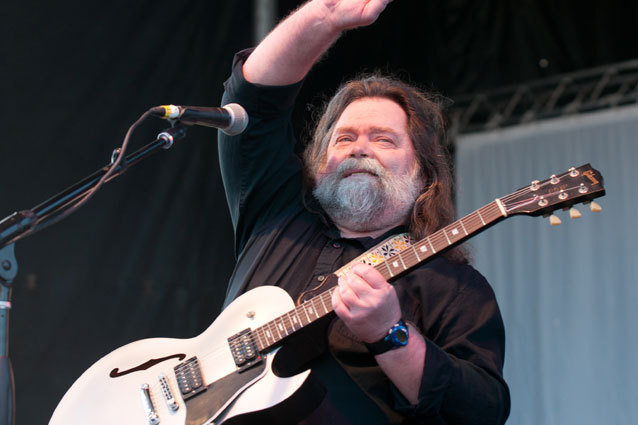

Arnold Wells/WENN

Arnold Wells/WENN

Roky Erickson has been a cult hero for so long that even the albums that introduced the Austin-based psychedelic survivor to an enthralled post-punk audience back in the 1980s are ready to be discovered by a new generation. The estimable reissue label Light in the Attic Records has revived Erickson’s three 1980s releases, The Evil One, Don’t Slander Me, and Gremlins Take Pictures, as CDs, downloads, and vinyl LPs that look and sound worlds better than their original incarnations.

Unfamiliar with Roky Erickson’s fascinating, tragic and ultimately uplifting story? Here’s what you need to know.

He Wrote A Garage Rock Classic

Roky first gained notice as the lead singer in one of the psychedelic era’s most notorious bands, The 13th Floor Elevators. Their albums — most notably 1966’s The Psychedelic Sounds of the 13th Floor Elevators and 1967’s Easter Everywhere — are legendary for openly proselytizing for the use of hallucinogenic drugs. But the Elevators’ first single (and all-time best song) is an Erickson-penned snotty little teenage kiss-off called “You’re Gonna Miss Me” that’s closer in spirit to the likes of “96 Tears” or “Dirty Water.” That song kept the band’s name alive when Lenny Kaye included it on the classic proto-punk compilation Nuggets: Original Artyfacts from the First Psychedelic Era in 1972, where generations of new garage rock fans first discovered Erickson.

He Made A Really Tragic Choice

Although it was the Elevators’ guitarist and primary songwriter Stacy Sutherland who was the driving force behind the band’s pro-hallucinogenics stand, that outspokenness made the entire band targets as far as Texas law enforcement was concerned. So when Erickson was arrested holding a single joint in 1969, he decided to plead insanity in an effort to avoid a potential decade in jail. Unfortunately, his three-year stint in a Texas mental hospital, which included heavy doses of both electro-shock treatments and anti-psychotic medications, left Erickson — who had had brief episodes of mental illness prior to being committed — far more mentally and emotionally damaged than he had been when he went in.

He Was A Post-Punk Cult Hero

One of the less attractive elements of the indie rock underground is that sometimes artists attract audiences more for their obviously unbalanced mental state (Daniel Johnston and the late Wesley Willis being two obvious examples) than for their actual music. While there’s no question that some of Erickson’s latter-day fans were attracted by the “Hey, lookit the crazy guy!” aspect of his story, the albums that Light In The Attic has just reissued stand up on their own musical merits. The Evil One (1981) most strongly features Erickson’s lyrical obsessions of that era, religious parables doused with creepy horror-movie imagery of zombies, werewolves and vampires. Don’t Slander Me (1984) is his most straightforwardly rocking effort and includes the glorious “Starry Eyes,” an utterly sincere power pop love song that sounds like the best single Buddy Holly never wrote. The patchwork Gremlins Have Pictures (1986) was gathered from live tracks and demos covering nearly a decade and is the hardest listen of the lot, both for its lo-fi sound and the clear evidence of Erickson’s steadily-worsening mental state in the fragmented songs. Still, even it contains the sterling live track “Song For Abe Lincoln,” a cockeyed optimist’s lyric set to one of the catchiest tunes he’d ever written.

He Got Worse…A Lot Worse

In the 1980s, Erickson announced that his body had been inhabited by an alien, and even got a notarized statement to that effect. Diagnosed as schizophrenic, Erickson lost interest in music by the late ’80s, and at the turn of the 1990s spent a stint in prison on mail theft charges that were eventually dismissed. During this period, a longtime fan who worked for Warner Brothers Records created the 1990 compilation Where The Pyramid Meets The Eye: A Tribute To Roky Erickson. Long out of print but easily available online, the set includes tracks by friends and fans including ZZ Top, R.E.M., T-Bone Burnett, Julian Cope and The Jesus and Mary Chain, not to mention now-obscure college rockers of the time like The Judybats, Thin White Rope and Poi Dog Pondering. The album both contributed royalties to Erickson’s all-but-depleted coffers and introduced him to the burgeoning alternative rock scene.

And Now He’s A Lot Better

In 2001, Roky Erickson’s youngest brother Sumner petitioned to take over his sibling’s guardianship due to the declining mental and physical state of their mother. With his mental illness more carefully managed thanks to that change and advances in medication, Roky Erickson returned to an almost-normal life that included live performances and, in 2010, a well-received comeback album, True Love Cast Out All Evil, with the help of fellow Austinites Okkervil River. A promo interview of Roky by Okkervil River frontman Will Sheff from that era shows an alert, witty, intelligent and introspective man in late middle age (he turned 66 in July) who more than possibly anyone else deserves the clichéd term rock and roll survivor.

More:

Alt-J Goes Ghostly and Slo-Mo for Fallon

Fleetwood Mac Before Buckingham Nicks

Fall’s 15 Most Anticipated Albums

From Our Partners: 40 Most Revealing See-Through Red Carpet Looks (Vh1)

40 Most Revealing See-Through Red Carpet Looks (Vh1) 15 Stars Share Secrets of their Sex Lives (Celebuzz)

15 Stars Share Secrets of their Sex Lives (Celebuzz)